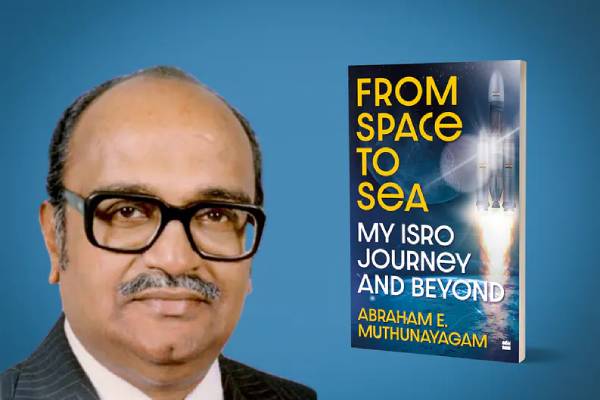

From Space to Sea: My ISRO Journey and Beyond: By Abraham E. Muthunayagam; Harper Collins; July 2022; 464 pages; hardback; Rs 799

The author was witness as well as participant in the first 3 decades of India’s Space programme. He brings a valuable insider-viewpoint to the story of how India attained mastery over key technologies like liquid propulsion. This is also a first look at the formative years of India’s ocean science and Antarctic programmes

August 28 2022: Before the Indian Space Research Organisation, there was the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR), the cross-over body that, Dr Vikram Sarabhai headed as he went about putting India on the map of Space Research.

In 1964, while pursuing a mechanical engineering doctorate at Purdue University, Indiana, US, a young student from India, Abraham E. Muthunayagam, saw an advertisement in the Indian embassy newsletter, inviting applications for positions in a new Indian Space Programme. He applied -- and almost a year later, was informed that Dr Sarabhai was in Washington DC and would like to interview him.

That same day, Dr Sarabhai hired six young Indian engineers for various positions at Thumba, on the outskirts of the Kerala capital which was to be the new home of India’s Space adventure. With a fresh PhD under his belt, Dr Muthunayagam joined – and remained with what became ISRO for another three decades. He weaves the history of india's journey into self-sufficiency in rocket propulsion into his own life. For most of his career in the Space programme, he specialized in liquid propulsion. His Wikipedia entry calls him the ‘Father of Propulsion Technology’ in India -- and after reading the first 250 odd pages, one can understand why. During his tenure as Director, liquid propulsion systems fuelled most rockets including the SLV3 programme.

After the tragic demise of Sarabhai in 1971, ISRO slipped smoothly into the Satish Dhawan era. Brahm Prakash was brought over from Atomic Energy by Dhawan to consolidate all Space programmes at Thumba under VSSC – the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre. By 1980 liquid propulsion emerged as the top technology for propulsion and Muthunayagam in his role as group director for propulsion was asked by Dhawan to head a new project for liquid propulsion .

There were three sub groups. The one relating to the Vikas liquid engine (which was to be the workhorse of ISRO launch vehicles for many years and) was headed by S. Nambinarayan – a name in the news these days again after the release of the film: “Rocketry: The Nambi Effect”, which tells the story of his own years with ISRO. the notorious espionage case foisted on him in the early 1990s, and its aftermath. The book devotes just a few paragraphs to the affair, but Muthunayagam implies that the then leadership of ISRO was remiss in leaving Nambi and his colleague D.Sasikumar to the mercies of law enforcement agencies with their own agenda, rather than clearing their names with a simple statement.

Polar satellite launch vehicles or PSLV harnesses solid propellent-based rocket motors and Muthunayagam documents the development of solid motor technology, dovetailing it into his personal contributions.

Through all these years, the holy grail of propulsion systems remained cryogenics – the use of rocket propellants at extremely low temperatures by using a combination of liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen which remain in a liquid state at temperatures of 183 degrees Celsius below zero and 253 degrees C below zero respectively. India tried all means to acquire this technology in the 1980s and 90s but had to contend with the closed club of nations which possessed this knowledge – and with the ability of the US to throttle the transfer of such technology even by adversary nations like the USSR by invoking what the Missile Technology Control Regime or MTCR.

The book chronicles the techno-political tussles to gain mastery in cryogenics technology – a tussle that left its mark in personal rivalries involving Muthunayagam and the people he believes thwarted his rightful claim to leadership of ISRO – including U. R. Rao, who became ISRO Chairman in 1984 and K. Kasturirangan who succeeded him in 1994.

When there was no head room for advancement in ISRO, Muthunayagam left – and ironically this launched a new chapter in the contributions of this versatile manager-scientist: as Secretary in the Department of Ocean Development, a post he was to occupy for 5 years from 1996.

This was a department that was set up in the Indira Gandhi years, headed by the charismatic S. Z. Qasim – he personally led the first Indian expedition to the Antarctic in 1981. Muthunayagam brought with him the strengths of planning and professional management that have always been a hallmark at ISRO: His stamp was seen in consolidating India’s programmes in Antarctica; the marine living and non-living resources programe; the efficient management and deployment of DoD’s research fleet and its programmes for coastal and marine management.

It was a giant leap from scanning the sky to scouring the bottom -- but Muthunayagam’s organizational strengths were again in full play and he left the department in 2001, a more structured, accountable agency.

This structured approach, creeps into his book too. The detailed layout of programmes, technologies and project time lines across the Space and Ocean development departments, may not make for smooth reading ( though the profuse illustrations in colour are a bonus). But precisely because so much of this has never been documented before, Dr Muthunayagam’s book will serve as a valuable resource and a fascinating insight into how India attained maturity in the twin arenas of Space and the Sea.- Anand Parthasarathy.

This review has appeared in Swarajyamag